Daniel Birnbaum är chef för moderna museet i Stockholm./Daniel Birnbaum, Director of Moderna Museet.

Bild: Pressbild

We want to shift the standard narrative of art

2013-09-20 | Katarina Rosengren Falk

CULTURE/INTERNATIONAL

Since Daniel Birnbaum and Ann-Sofi Noring took over the directorship of Moderna Museet in Stockholm, it seems to be their deliberate strategy to integrate a gender perspective in the Museum’s exhibitions activities. Is this so?

Katarina Rosengren Falk put this question to Daniel Birnbaum in an exclusive discussion on feminism, regeneration and the future.

For some time now, Sweden has had an art museum that strives consistently to highlight women artists. Hilma af Klint, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Yael Bartana, Keren Cytter, Siri Derkert, Cecilia Edefalk, Sofia Hultén, Jacqueline de Jong, Mary Kelly, Jutta Koether, Klara Lidén, Lee Lozano, Tala Madani, Alice Neel, Niki de Saint Phalle, Doris Salcedo, Isa Genzken and Ulla Wiggen have all been featured at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and sometimes in Malmö, in the last few years. This sounds like a feminist utopia. But since Daniel Birnbaum and Ann-Sofi Noring assumed the directorship of Moderna Museet on Skeppsholmen in Stockholm, there seems to be a deliberate strategy to integrate a gender perspective in the Museum’s exhibitions activities. Is this so?

– Yes, it is our deliberate strategy. I'm surprised myself by all those names, and yet, a few have been left out. Since 2010, the year Ann-Sofi Noring and I took over, we have had considerably more solo exhibitions with women than with men.

Where do you personally get your inspiration? Impressions from the international art scene? An acute awareness of the massive male dominance in the Museum collection? Or is there something else that drives you?

– It’s about gender equality as a matter of fairness, of course. About dealing with male dominance. The fact is that we are the only major museum that is actively engaging with this issue internationally. But it’s also about seeing art from new perspectives. At Moderna Museet we strive constantly to shift the standard version of how modernism evolved – sometimes in small ways, sometimes radically – by focusing on artists who have been somewhat obscured. These artists are frequently women. The fact that, for the fourth year running, we now have more solo exhibitions with women artists than with male artists is thus not merely an expression of our ambition to redress this imbalance, it is also indicative of our desire to present alternative narratives of how art developed. The major European museums are male-dominated, so this is also a way for us to be different and more exciting. That’s the real driving force.

The Hilma af Klint exhibition is an excellent example of how gender theory can be applied in practice. By highlighting this previously obscure artist, you have changed the picture of both Hilma av Klint and her era. But how was the exhibition Hilma af Klint – A Pioneer of Abstraction received? It is still argued, for instance, that af Klint did not actively strive to change the concept of art, and that this is why she was forgotten. But would it have been possible for a woman artist to make an innovative voice heard on the elite art scene at the time? Are there any examples of this? From a feminist perspective, it could be interpreted as a strategy and a creative decision to choose seclusion in order to focus on your art. Do you think this may have been the case?

Hilma af Klint - A Pioneer of Abstraction at Moderna Museet earlier this year.

– When it comes to radical shifts in the standard narrative, the Hilma af Klint exhibition has a good chance of achieving that. No other exhibition at Moderna Museet has ever received as much international attention. It was reviewed by nearly all major European newspapers, and even by the New York Times. But does she really belong to the early avant-garde? I don’t think so, because she created her own networks instead of setting off for Paris or Berlin to participate in her era as we know it. She preferred to create for the future.

Do you think there are other outsider artists, so to speak, of the same calibre as af Klint, who remain to be “discovered” to complement the canon?

– Perhaps not like af Klint, because she was unusually secretive. But by presenting a painter like Jutta Koether last year, instead of, say, Martin Kippenberger, we gained a new perspective on German painting. Not necessarily a truer perspective, but one that has not been repeated insistently by countless museums all over the world. The major exhibition of Eva Löfdahl was primarily a presentation of a great Swedish oeuvre, but by situating her art in a rich context of literature, dance, music and philosophy, it served as a prism through which we could look back at the generation that emerged in the 1980s. That certain artists can serve as prisms in which the artistic and political ambitions of an entire era becomes visible is a concept that has informed all our endeavours. By choosing Yoko Ono, one of extremely few women artists in the fluxus movement, we gained not only a specific insight into this particular group but into an entire generation.

Ann-Sofi Noring and Daniel Birnbaum are the Directors of Moderna Museet.

How do you relate to the fact that the Moderna Museet collection consists of a devastating majority of white, so-called cisgender men? Will this change as a consequence of your work?

– It’s hard, naturally, to change the gender balance of such an enormous collection that reaches more than a century back in time. Instead, presenting a strong female perspective will give us a richer understanding of history. We don’t want to present a fraudulent version of history, but we want to understand and present it in a richer way. Most of the modernist groups were dominated by men, that’s a fact that we don’t want to deny. It’s true not only of cubism and Picasso or surrealism and Dalí. Take the situationists, for instance, the radical political and artist organisation, headed by Guy Debord, which formed what is often considered to be the last European avant-garde. A closer look reveals women members. The situationists, for instance, included the writer Michelle Bernstein, one of the group’s founders, and the painter Jacqueline de Jong, editor of The Situationist Times. Last spring, they both visited the Museum, de Jong for an exhibition, and Bernstein for a presentation of All the King’s Horses, her roman à clef about the situationists which had been published in Swedish translation by the OEI in association with Moderna Museet. American pop art is also predominantly male. However, Elaine Sturtevant, who has received international attention in recent years, was an enigmatic artist who operated in the same circles as Andy Warhol and was a friend of both Jasper Johns and Claes Oldenburg. In her art, she pursues the concepts of repetition and reproduction to even greater lengths than her male colleagues, shedding new light on her entire generation’s ideas on sampling and appropriation of visual material. In that sense, the Sturtevant exhibition was also a prism through which an artistic and intellectual landscape appeared in a new way. History is not carved in stone once and for all; it is rewritten continuously – by all of us who work with art, as researchers and exhibition producers. And by the audience, all the people who are ready to encounter it from new angles. Ann-Sofi and I use the exhibitions to set a kind of agenda. The collection is there like an infinitely prolific backdrop, but it can be approached in many different ways, and if we highlight major women artists, this will enrich history as a whole. I am so happy we have seminal works by Louise Bourgeois; through her, we can view surrealism without constantly rehashing Dalí and Duchamp. And I’m happy we have what is perhaps Meret Oppenheim’s most important work, you know, those remarkable shoes trussed together in a bizarre little sculpture.

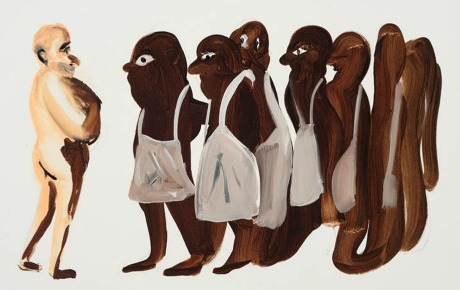

Devouring Mother, by Nikki de Saint Phalle.

I take it that by a “fraudulent version of history” you mean women or other artists outside the norm cannot be “invented” as an afterthought, but both the Hilma af Klint exhibition and the one about Niki de Saint Phalle still change our idea of a woman artist, and thereby influence the discourse. Art history is also altered by highlighting the white male hegemony in art and other fields. Problematising power, norms and canons is also one of many ways of promoting gender equality. This is an urgent matter in the ongoing transformation of Swedish feminism, where everything from gender theory to activist practices is being updated, or is in need of updating. There is currently an inspiring critical boom relating to white hegemony, binary gender categories, heteronormativity, transphobia and many other feminist concerns. Alongside this, questions of including performativity, intersectional identity and many other issues are beginning to be formulated and expressed by artists such as Mika Rottenberg. Do artists who experiment with identity and performativity primarily follow in the pioneering footsteps of other artists, or are they mainly inspired by new theories and practices?

– When I was studying in New York in the early 1990s, more was written about Cindy Sherman than about any other artist. Rosalind Krauss was my professor at Columbia, and she used Sherman’s images to discuss the Self as a construct, inspired by Roland Barthes and Jacques Lacan. There were many others who wrote about Sherman even in those days, based on ideas from Judith Butler. But the remarkable thing about great artists is that they never just illustrate theories. We can, of course, apply psychoanalysis and queer theory to Sherman’s works, but it cannot comprise them entirely. Has Sherman even read Lacan? I haven’t dared ask, but I doubt it.

No, that is something that distinguishes truly inspirational art, that it is often evasive and intrusive at the same time. Also, there is no way of translating it directly into words or verbal explanations, for the artist, I guess, or for the viewer or critic. So, what do you have to say about the forerunners of artists such as Mika Rottenberg and Tala Madani?

– Duchamp created his alter ego Rrose Sélavy, and thereby became the first overtly queer figure on the art scene. Without Rrose Sélavy I’m not sure David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust would have been possible, and Warhol’s transvestites may not have had the same impact on other artists on the art scene without inspiration from Duchamp. Two examples of artists who work with politics that in various ways relate to the construction of identities are Tala Madani and Cindy Sherman, whom we are featuring in an exhibition this autumn. Madani creates rather fantastic paintings about power structures and masculinity. Her ritualistic, often absurd situations oscillate between figuration and abstraction, and they can be quite provocative. I don’t know of any other painter who examines male roles as frankly.

And in Sweden, what’s the situation like here? From a feminist perspective it is both heartening and also surprising to find artists who call themselves feminists nowadays, and whose careers don’t seem to be damaged by it, such as Rebecka Bebben Andersson, who is still at the Royal Institute of Art. It hasn't always been like that, in the compact masculinity of the art scene.

– If we look at the Swedish situation, we find that many of our most internationally successful artists are women: Karin Mamma Andersson, Cecilia Edefalk, Nathalie Djurberg, Klara Lidén, Sofia Hultén. Whether all these women artists consider themselves to be feminists I don’t know, but it is obvious that the art scene has changed. A critically-minded person might perhaps ask how important this whole topic is, in relation to other power structures. Wouldn’t it, for instance, be more interesting to study these activities in terms of diversity? Aren’t we absurdly white and West-oriented? Yes, we are. I’m pleased that we are currently the major museum in the world to highlight the most women, but these other topics are an enormous future challenge that is just as important. And it’s not about believing we have to take an interest in cultures that are far, far away. On the contrary, this entire diversity exists here in Stockholm, and we are ready to take a closer look at what’s going on.

If you mean that we have reached a stage where we can leave the gender equality perspective behind, I think you’re wrong. But it’s necessary to combine all forms of feminism with other analyses. A process of change, whether it relates to research or practice, that is based on a heteronormative, white hegemonic, two-gender model, is not only obsolete but counter-productiove, as Black Feminists’ critique of Slut Walk and other feminists’ criticism of Femen clearly demonstrates. One way of approaching these issues is by using the intersectionality perspective, which focuses on discovering the intersections between theory and practice. But the art sector has long been proud to claim that it is globalised. Biennials and other recurrent exhibitions of contemporary art are said to have changed the terms for curators, critics and others, including political and financial players. Have these changes meant that the events and art elite have become/taken part in new places and contexts through this literal form of globalisation?

–Yes, the days when there was a dominating geographical centre for art are gone. That realisation is the starting point for a series of seminars next year in Stockholm and Amsterdam on artists who create links between continents.

To be even more specific, can you name any examples of exciting artists whose work focuses on these issues?

Dirt, by Tala Madani.

– Many. Tala Madani, for instance, whom I mentioned earlier, who grew up in Iran and now lives in the USA. Her paintings and animations comment with humour and seriousness on power structures at different levels. This autumn, we are also featuring an exhibition of Christodoulos Panayiotou from Cyprus, who has a background in choreography and anthropology and combines the methods of the scientist and choreographer. The Brazilian artist Rivane Neuenschwander has worked with a group of Swedish students to design new furniture for the Museum’s main entrance, an ambulating project that was based on the encounter between Nordic folk crafts and contemporary everyday life in Brazil. Next year, we we also have a major retrospective on the Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco, who moves between three continents and as many languages. His subject matter is inspired by Latin American traditions, and his works play with the readymade concept or are presented in the style of a natural history museum. He’s fantastic! Meriç Algün Ringborg is active in Istanbul and Stockholm and her works blend experiences from two different parts of the world and her passages between them. Meanwhile, Georges Adéagbo from Benin is engaged in collecting objects from the outskirts of the city, and various items made by local craftsmen. Adéagbo then combines his material into monumental collages, which I hope we will be able to show next summer. Madani, Panayiotou, Neuenschwander, Orozco, Algün Ringborg and Adéagbo are all artists of this rather new kind. Homeless or at home in many places. They create links between different parts of the world and contribute to redrawing the map.

So what will the future be like at Moderna Museet? Will you continue to complement the canon and make art more inclusive?

Cindy Sherman is coming to Stockholm and Moderna Museet in October.

– I believe we are at a point in time when art museums simply have to constantly reconsider their activities. Maps are still being redrawn, and we must scrutinise our own history in the light of new knowledge in a globalised world. We will continue showing young women artists. There are many who have exhibited more internationally than at home, Nina Canell, for instance. And we will highlight artists who have been a bit neglected. Many of them are women, such as Lena Svedberg. And then, of course, we have the truly great international women artists. I hope we can achieve a really good exhibition of Louise Bourgeois; she is, after all, unbelievable. We have two fine works by her in the surrealism exhibition, but our visitors deserve a more thorough presentation. And then we are contemplating Marina Abramovic – a lot has happened in her oeuvre recently. Perhaps she ought to be invited? The last time was long ago now. But in the immediate future, we have Cindy Sherman, one of the world’s most important artists. Her images can be cool and suave, but also horrific and revolting. They want to remind us about all the things the polished female facade has to hide: body fluids, vomit, slime and blood. Mould and putrefaction increase our disgust. Perhaps they can be read as reminders of the censored and psychologically repressed side of the feminine construct. Cindy is here now, hanging her pictures. This will be the most important exhibition in Sweden this year.

Kommentarer

Du måste vara inloggad för att kunna lämna en kommentar.

MEST KOMMENTERAT

SENASTE KOMMENTARERNA

Om Var Grupp 8 en feministisk organisation?

Om #bildskolan 21: Att äta Den Andre

Om #bildskolan 21: Att äta Den Andre

Om Porr handlar om betalda övergrepp

Om Nobels fredspris till kampanj för att avskaffa kärnvapen

Om Feministiskt perspektiv öppnar arkivet och startar på nytt!

Om Rödgrönt ointresse för fred och nedrustning borde oroa många

Om Var inte målet att vi skulle jobba mindre?

Om Feministiskt perspektiv öppnar arkivet och startar på nytt!

Om Feministiskt perspektiv öppnar arkivet och startar på nytt!

MEST LÄST